Questions to support new mums

By Jane Fisher

There's an art to finding out if a woman needs help for postnatal depression.

Perinatal depression (PND) and anxiety are common and thought to affect up to one in seven women who are pregnant or have recently given birth.

Given that about 300,000 women give birth each year in Australia, PND could affect about 42,000. The condition costs our economy an estimated $433 million in direct service provision and lost productivity.

PND and anxiety can adversely affect cognitive, social and behavioural dimensions of early childhood development, so early diagnosis and management are beneficial.

GPs are well-placed to help women understand their experiences and identify the possible relevant risk factors for PND and anxiety. Women who experience persistent worry or low mood when they are pregnant or have recently given birth will usually turn first to their GP for help.

Empathy is valuable. Women tell me they appreciate it when their GP asks about their circumstances as well as their symptoms. It’s helpful for GPs to take a psychoeducational approach, in which the links between risks and symptoms are explained and addressed. If well-equipped with the knowledge of risk factors, GPs can question women, help them make sense of their feelings and work towards a solution.

Six risk factors for PND

1. Parents

Ask the patient about her parents using two open-ended questions:

a) “Can you tell me a bit about the family in which you grew up?”

Usually a woman will tell you if there has been divorce, premature bereavement or maltreatment. This can highlight the need for more specific questioning.

b) “Where are your parents now? Are they available to offer you practical assistance or care and support?”

The answer will tell you whether or not the woman has family she can call on when she needs support.

2. The partner

I ask the patient to tell me the story of meeting her partner, deciding to have a baby, and his response to the pregnancy and the birth. That will give you a sense of whether he’s committed, involved, sensitive and helpful.

The narrative might be that he was ambivalent about the pregnancy, not very involved, and not particularly available since the baby’s birth. This will give you another angle of inquiry. It’s always important to assess whether the woman is experiencing any coercion or intimidation.

I usually tackle that by asking how things are with their partner at the moment. What his sleep is like, if he is drinking and how much, if he loses his temper. This step leads to the question: “Do you ever feel frightened of him?”

3. Peers

I ask whether the woman knows anyone else with a baby. I ask if she has she joined or been included in a mothers’ group and, if so, how it is going.

Does she feel welcome and included? Does she want to go? Invariably, women who get miserable will tell you that their mothers’ group hasn’t worked for them.

4. Professional support

I ask mothers about their relationship with their maternal and child health nurse, whether they have any paid help at home, and if they have any persistent postpartum health problems they are seeing a specialist about.

The woman may be extremely tired, have an unhealed perineum, breast problems, caesarean pain, incontinence or any number of health concerns that can adversely impact her mental state.

5. Psychiatric history

I will ask the woman if she has ever been diagnosed with, or treated for, alcohol or drug dependency, an eating disorder, previous depression, or adjustment/anxiety disorders.

Each of these answers provides the doctor with an entry point to discussion. It’s crucial to know how long ago the problem occurred, what treatments were offered and whether they helped.

6. The baby

How much does the baby cry and what does she do to stop the crying? What works or doesn’t work? What is the baby’s sleep pattern like? What sort of daily care routine is there?

A baby with dysregulated sleeping, feeding and crying is difficult to care for, and in this situation women lose confidence and wellbeing declines.

If she describes chaotic, unpredictable days, this warrants investigation.

What next?

The next step is to work with the woman on deciding the most pressing matter on the above list. The easiest starting point is the baby. If the baby is helped into a more regulated pattern, the woman can begin to think more clearly about the other problems.

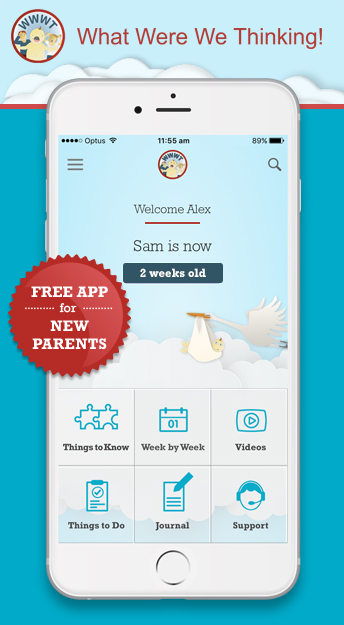

This is where a parenting app developed by Monash University and Jean Hailes can assist. It is called What Were We Thinking! (WWWT!) based on the evidence-based intervention program of the same name, this free app, funded by the Australian Government, teaches new mothers and fathers both practical skills for settling babies and ideas to help them adjust to changes in their relationship that parenthood can bring.

It gives parents the knowledge, skills and reassurance to provide a structured environment, and introduces the feed, play, sleep routine. It also helps GPs to work through these conversations and activities alongside the parents. Get your patient to document her progress with the WWWT! app and to share it with you. This is essential and means she is not lost to follow-up. Referral is important. If the mother feels she can’t do it on her own, suggest a residential early parenting program.

Visit www.whatwerewethinking.org.au and download the free app on App Store (iOS) and Google Play (Android).

This article first appeared in the Medical Observer. Read past Medical Observer articles.

Professor Fisher is an academic clinical psychologist. She consults to the Masada Private Hospital Mother Baby Unit and is an expert adviser to international agencies includ-ing WHO, UNICEF and the United Nations Population Fund. Her research focuses on gender-based risks to women’s mental health and psychological functioning, from adolescence to mid-life.

Posted in: Baby 0-4 weeks Baby 13-16 weeks Baby 17-20 weeks Baby 21-26 weeks Baby 5-8 weeks Baby 9-12 weeks Health Professionals Late pregnancy Your needs